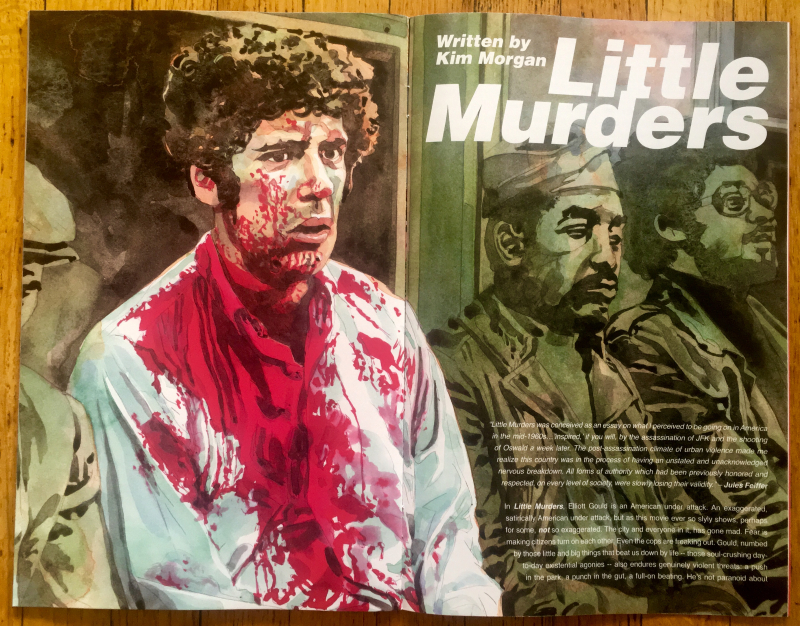

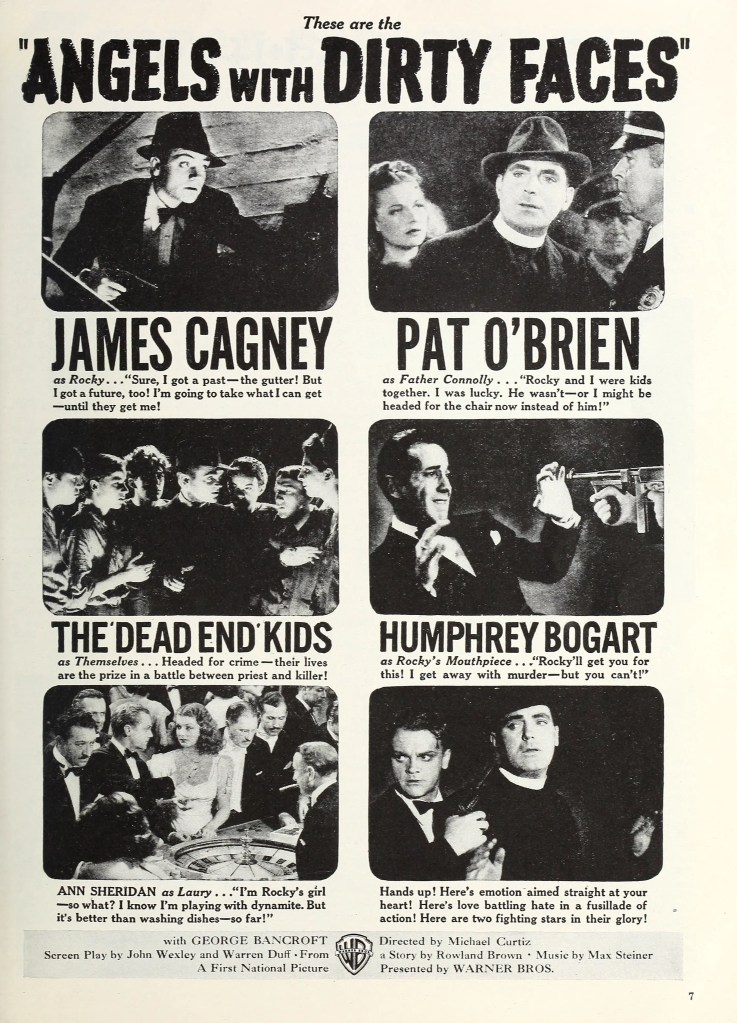

Chuck Your Chest Up to the Wood : Angels with Dirty Faces

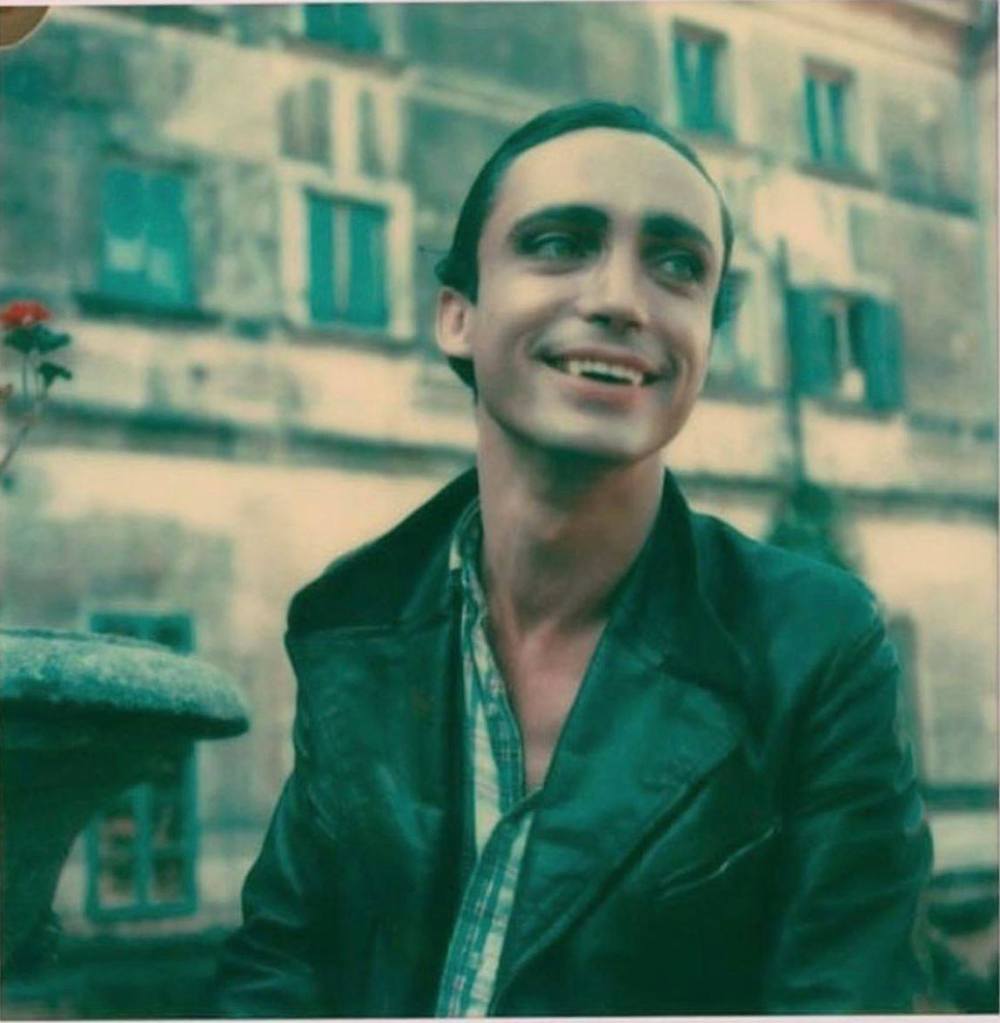

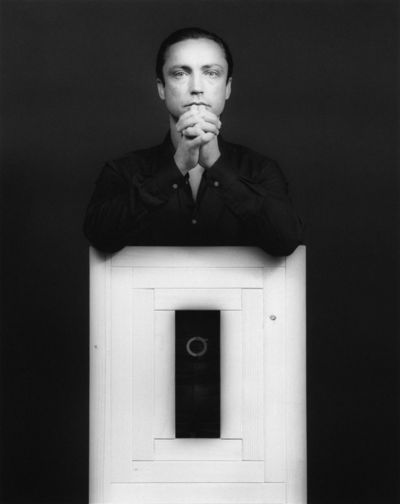

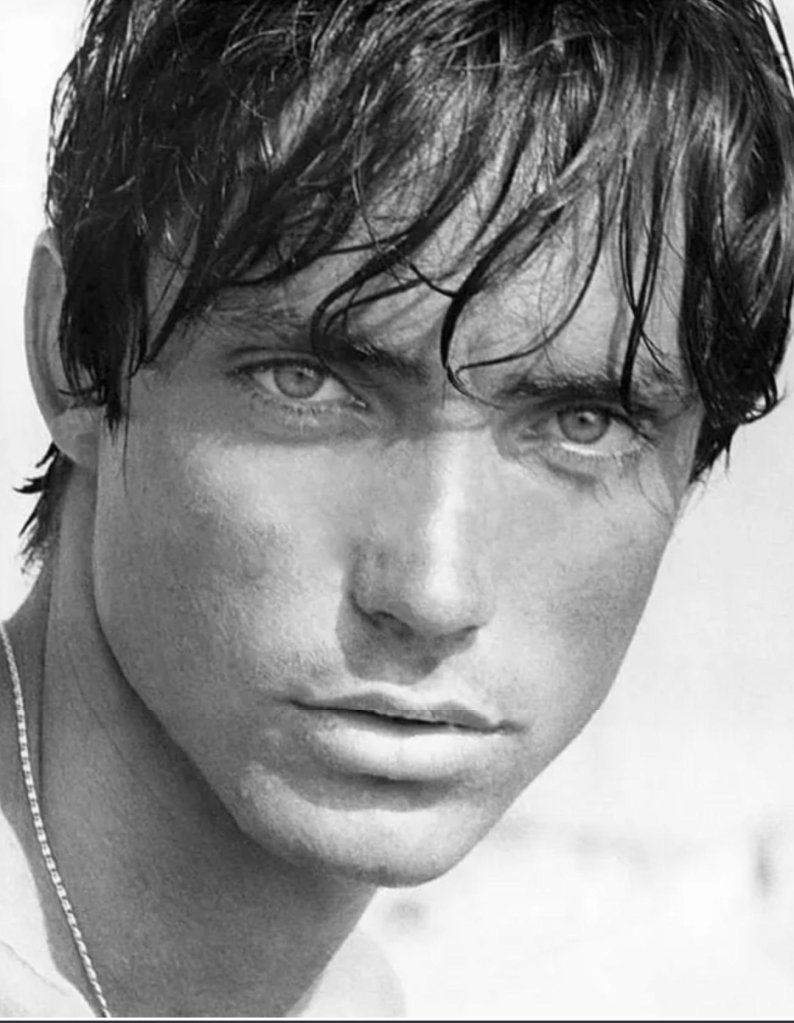

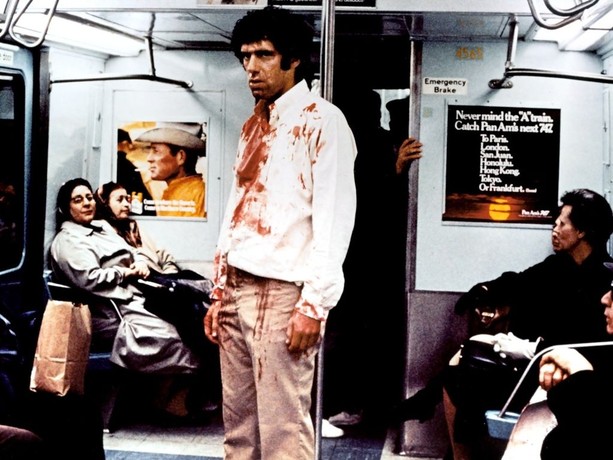

“The character I played in the picture, Rocky Sullivan, was in part modeled on a fella I used to see when I was a kid. He was a hophead and a pimp, with four girls in his string. He worked out of a Hungarian rathskeller on First Avenue between Seventy-seventh and Seventy-eighth streets—a tall dude with an expensive straw hat and an electric-blue suit. All day long he would stand on that corner, hitch up his trousers, twist his neck and move his necktie, lift his shoulders, snap his fingers, then bring his hands together in a soft smack. His invariable greeting was “Whadda ya hear? Whadda ya say?” — James Cagney from “Cagney By Cagney”

“You’ll slap me? You slap me in a dream, you better wake up and apologize.” – Rocky Sullivan

We love Rocky Sullivan.

And not just love him because we’re Spit/Spike/Bim/Slip/ Muggs or whomever else Leo Gorcey embodied as his days as a Dead End Kid/East Side Kid/Bowery Boy — but we love him as an audience watching Angels with Dirty Faces, delighting in the pugnacious charm of James Cagney.

We love him just as much, even more, perhaps, when he’s fried at the end of the picture. He turns, or, rather, pretends to be (we don’t know which one for sure) yellow. He howls for mercy as the jailers drag him to the electric chair in that gorgeous, horrifying, shadowed death chamber sequence:

“No! I don’t want to die! Oh, please! I don’t want to die! Oh, please! Don’t make me burn in hell. Oh, please let go of me! Please don’t kill me! Oh, don’t kill me, please!”

Rocky is either really scared or a really good actor or both – we feel like crying whichever way it goes. Some of us do cry when Rocky gets it. The guard sounds almost Shakespearean once they finish him off:

“The yellow rat was gonna spit in my eye” (“Why dost thou spit at me?”).

Pat O’ Brien’s priest Jerry Connolly, while so visibly moved at Rocky’s cowardice or courage, practically sees the skies opening, angels singing, readying for Rocky’s hoofing to heaven. Rocky cannot be burning in hell. No. There’s no way God is going to allow Satan a Rocky, and not after Rocky granted Jerry that kind of courage, a courage “born in heaven,” getting straight with God. Unless God is a double crosser– lost a bet with Satan. We hope not. If we believe. Do we believe?

We believe in Rocky.

A tear drops from gentle Jerry’s eye and we, somehow, hold nothing against him for asking Rocky to ham it up before death – a pretty unreasonable request if you ask me – and Rocky says so too: “You ask a nice little favor, Jerry. Asking me to crawl on my belly the last thing I do.” Indeed.

And indeed, when we think about the Hollywood production code, led by Catholic censor Joseph Breen, meddling with movie morality, passing on his suggestions/demands especially here — as this is, a movie in 1938, following the friendship between a priest and a gangster — was of keen interest to him. Breen was concerned earlier gangsters were shown in too glamorous and sympathetic light – he worried those rebels, like a pre-code Tom Powers (Cagney, in The Public Enemy) or Tony Camonte (Paul Muni, in Scarface) were leading the public astray. They were just too damn sexy and exciting for the depression-era audiences and he feared they sided with their rejection of what would be deemed a square society. A society of suckers because, look how bad things are anyway? Why go straight?

But Breen’s not really getting his wish granted with Michael Curtiz’s entertaining, moving, at times masterful Angels with Dirty Faces (gorgeously shot by cinematographer Sol Polito), even if he thought he may have. Sure, we have a priest “winning” in the end – if you call that winning. And, yes, we’ve got a melodrama about good and evil and those society are most worried about – impressionable children. The young ones who hero worship gangsters, the kids who, quite understandably, wonder why in hell they should work as hard, and for peanuts, like their parents do. Or, maybe, their parents aren’t working at all (here, the Dead End Kids – Billy Halop as Soapy, Bobby Jordan as Swing, Leo Gorcey as Bim, Gabriel Dell as Pasty, Huntz Hall as Crab, Bernard Puntzley as Hunky – I think I got them all). But nothing can erase the unescapable magnetism of Cagney’s Rocky Sullivan, no matter what the headline hollers after his death: “Rocky Dies Yellow: Killer Coward at End!”

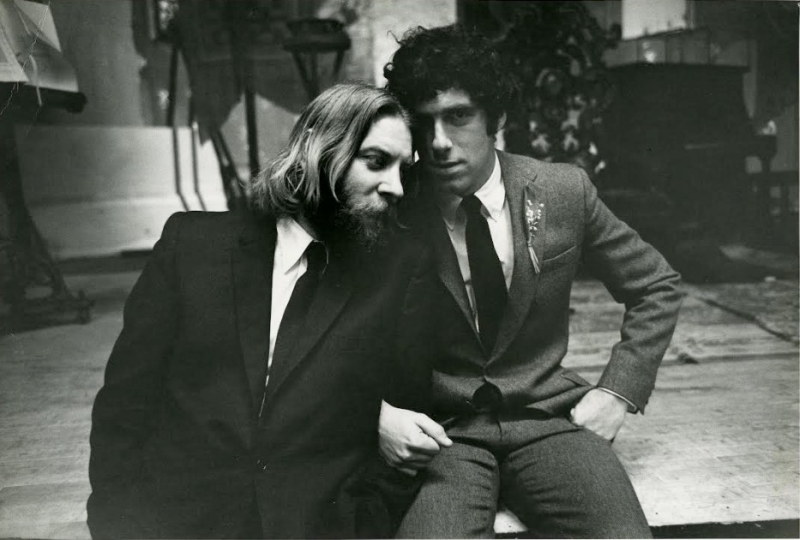

Those kids, led by Soapy, are introduced to Rocky’s swagger the moment they steal his wallet. Rocky’s out of prison and back to his criminal ways and, not knowing that this is THE Rocky Sullivan, the little toughies rob him. He figures it out quickly, and heads down to their hide-out, a place that used to be his old hide-out with his pal, Jerry, who was once a hooligan like him, and is now a priest. We’ve learned that Rocky was chucked in juvenile detention when he couldn’t outrun the cops like Jerry could (you’ll be reminded of this in the film’s final heavenly line). And, so, Rocky turned deeper into crime. Jerry turned to God. Endearingly, they remain friends.

The scene where the kids figure it out is so seductive and charming, that, if you haven’t fallen in love with Cagney already, you will right then and there. “Next time you roll a guy for his poke, make sure he don’t know your hideout,” Rocky says to them, not even angry, just kicking them in the pants for being so stupid, laughing along because he used to be like them. He puckishly winks as confirmation of being Rocky, rather than announcing himself, he doesn’t need to. Swing exclaims: “It’s Rocky Sullivan! We tried to hook you! What a boner!”

Well, now the kids idolize him. What is Father Jerry going to do? He tries to get Rocky involved as some kind of good influence – but Rocky is already back to his criminal ways, getting in even deeper with his crooked, and it turns out, quite quickly, murderous, double-crossing lawyer, Jim Frazier (Humphrey Bogart, terrific here), who is the picture’s real villain. Frazier tries to get Rocky killed, who strikes back (which isn’t so surprising). The corrupt lawyer will later even put a hit on Jerry, a damn priest – we already know that Rocky can’t go that far. (Can you imagine how less sympathetic Rocky would have been had he agreed to that plan? Where was Breen on all this? Probably secretly seduced by Rocky too…).

Rocky’s also got a likable love interest in beautiful, spirited Ann Sheridan who runs the boarding house Rocky initially rents once out of stir. These are good people around him – and he riffs and physicalizes with the kids with such ease and, at times, brilliant hoofer that Cagney was, a plug ugly grace. There’s famous lines here, and then there’s just wonderful, rapid-fire little toss-offs too, like when Rocky asks the kids to sit down to lunch. He instructs, “Chuck your chest up to the wood.” It seems to mean a few things by the very way Cagney utters it – sit down, listen to me, deal with life, grow the fuck up. Oh, and eat your lunch.

So, when it’s all over, well, I just don’t believe that these kids have really lost respect for Rocky, even if they appear so. O’Brien, with his lovely eyes and genuine humanity is still likable, we don’t want him to fail the kids, but we also don’t think his plan will work. After all, this is Cagney as Rocky. This is “Whadda ya hear! Whadda ya say!”

They’ll get over the coward bit. They may even begin to disbelieve it. And they may not turn to crime, and that’s good, but they may have learned some more know-how about life. They may now really- and not just to eat their lunch- chuck their chests up to the wood.